1995-96 was the last full season of Sergeant Wilko’s eventful reign at Elland Road. His influence over the club was crumbling amid rumours of money problems, takeovers and dressing-room discontent, a tale that would doubtless strike a chord with Messrs. Grayson and Warnock of more recent vintage. This was a season that had started off with a flurry of Tony Yeboah thunderbolts and some impressive results and performances which appeared to promise much. Sadly though, it would peter out in a shocking late-season run following a League Cup Final humiliation at Wembley, courtesy of Aston Villa. Howard Wilkinson was a dead man walking from that time on.

Worrying signs of defensive frailty and general ineptitude had been all too obvious just the previous week at Hillsborough. United had succumbed spinelessly to a 6-2 defeat at the hands of an unremarkable Sheffield Wednesday side and – all bravado aside – there wasn’t much optimism in the hearts of the faithful as this fixture against the arch-enemy loomed.

It was certainly a different Christmas Eve for me. I hadn’t exactly led a sheltered life up to that point, but this was the first time – and the last, to date – I’d ever risen the day before Christmas to bacon sandwiches at 6 am, closely followed by numerous Budweisers with the Sunday papers in a fan-friendly pub, as we waited for our “Scum Match Special” mini-bus. The queasy feeling before any match against “Them” was therefore multiplied by unaccustomed early-morning grease and alcohol, and I was feeling several shades of not-too-good as we set off for Elland Road. It was an 11:30 kick-off, live on Sky, and it promised either to make or break the whole of Christmas for us fans, and for our hopeful families.

The situation between the Uniteds of Leeds and Salford is one of a legendary mutual animosity, even at the best of times. Let’s not mince words here, the two sets of fans hate loathe and detest each other, and open warfare is the norm. Revisionist football pundits would have us believe that this is strictly a one-way affair, but you only have to tune into one of Sky’s glitzy live TV love-ins for a Man U match, and whoever they are playing, our Home-Counties friends are in full voice with their “We all hate Leeds scum”. Even Alex Ferguson, the Red Devils’ not-altogether-likeable manager, makes no bones about it; some of his more coherent sound bites feature his opinion that Elland Road is “the most intimidating arena in Europe”. He’s also stated that going to Liverpool is nowhere near as bad as going to Leeds; clearly, he’s never been for a late-night pint in Old Swan or Dodge City.

So, Yuletide or not, the usual poisonous atmosphere was in evidence as the two teams walked out before a 39801 crowd that overcast morning. Just as Leeds were smarting from their Hillsborough debacle, so Man U were struggling to emerge from a poor run, winless for a month and dispatched by Liverpool the previous week. This seasonal fixture was a chance of redemption for both sides.

By kick-off time, I was starting to feel properly ill, and in dire need of a pick-me-up. This arrived in a most unlikely form after a mere five minutes, when a Leeds corner swung over from the right. Richard Jobson rose on the edge of the area to head towards goal, where David Wetherall, lethal against Man U in the past, was challenging for a decisive touch. But that touch came instead from the upraised, red-sleeved arm of Nicky Butt – and referee Dermot Gallagher’s whistle sounded for a penalty.

Peering from the Kop at the other end of the ground, through an alcoholic fug, I could hardly believe my eyes. Leeds just didn’t get penalties against “Them”. It would happen the other way around alright, too often, and even from three yards outside the area but this was unprecedented, since our Title-winning year anyway. Steve Bruce evidently thought it was just too much to bear, and screamed his violent protests into Gallagher’s face, having to be restrained by Gary MacAllister, who appeared to be trying to explain the rules to the furious defender. The guilty look on Butt’s face, though, spoke volumes. MacAllister placed the ball on the spot, and sent it sweetly into the top right corner for 1-0, giving Peter Schmeichel not even the ghost of a chance. The celebrations were raucous and deafening as the Elland Road cauldron exploded with joy – and inside my skull, the trip-hammer of a beer-fuelled headache pounded away anew, utterly failing though to banish my smile of delight.

Leeds had the bit between their teeth now, and Brian Deane was suddenly clear for an instant outside the right corner of the Man U penalty area, played in by a cute pass from Carlton Palmer. Schmeichel was out swiftly to smother the chance, but Deane managed to dink the ball over him, only for it to clip the crossbar and bounce away to safety. A two-goal lead at that stage would have felt unlikely yet deserved, as Leeds United had been on the front foot right from the off. Soon, though, a lesson was to be delivered about what happens when you miss chances against this lot.

The unlikely culprit as Leeds were pegged back was Gary Speed. Receiving the ball in the left-back position, he tried to beat Butt instead of clearing long, and was robbed of possession. Butt looked up, and placed a neat pass inside to Andy Cole, whose efficient first-time finish levelled the match. Suddenly, my headache was even worse, and I was starting to wonder about the fate of my breakfast too. Time for another reviving injection of optimism as Leeds surged forward, and Speed so nearly made up for his defensive error, playing a one-two with Tomas Brolin which gave him space to put in a right-foot shot that went narrowly wide.

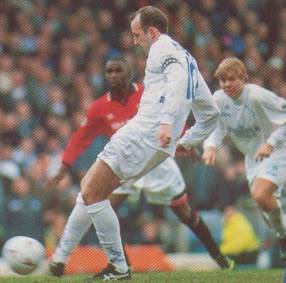

The game had settled down by this time, and both sides were showing enough ambition to feel that they were in with a chance of victory. Leeds though had thrown off their Sheffield blues, and attacked with verve and purpose. Now, a defensive position was coolly handled by Gary Kelly, finding the time and space to launch a long clearance forward, where Brolin headed on. The ball was loose, and surely meat and drink for Man U’s international defender Paul Parker – but he inexplicably let it bounce over his foot. Yeboah pounced on it like a hound on a rat, and he was away, surging towards goal with ex-Leeds defender Denis Irwin backing off. Yeboah in this mood was usually irresistible, and sure enough none of Irwin’s careful jockeying could prevent him from finding that vital half-yard of space. The gap appeared, Schmeichel came out to block, and Yeboah clipped the ball sumptuously just out of the Danish ‘keeper’s reach, up and over to nestle in the far corner of the South Stand net.

Again, that explosion of noise and joy, again my fragile system was assailed by the rough-and-tumble of riotous celebration. 2-1 up against the team we loved to hate; the cockneys at the far end were suddenly silent and morose. “You’re not singing anymore!” we blasted at them, and indeed, little would be heard from the away fans for the rest of the game.

The second half was another tale of give and take, both sides able to cause trouble up front, but both seemingly capable of dealing with all that was thrown at them. The onus was on Man U to retrieve a losing situation, but Leeds were rarely in great trouble, and as the game entered its final quarter there was unprecedented optimism that we could close this one out, and enter Christmas on a real high. Leeds weren’t simply sitting back and absorbing pressure – and the maxim of attack being the best form of defence was to serve them well. On 73 minutes, Jobson made a foray down the left, and was fouled by Cole chasing back. The resulting free-kick was played to MacAllister in space in the middle of the park, and he swiftly moved it out to the right wing. Brolin picked up possession, and then slipped the ball to the overlapping Palmer, who surged into the box, and then turned past Irwin to set up Brolin again on the edge of the area. The much-maligned Swede, making the contribution I best remember him for, chipped the ball sweetly first-time, standing it up just around the penalty spot, where Deane’s exemplary movement had won him the space to rise and plant a firm header past a helpless Schmeichel into the net. 3-1 and finis.

After the game, and before the Yuletide celebrations could begin in earnest, other traditions had to be observed. Ferguson, naturally, had to moan about the penalty. “It was a very surprising decision, given in circumstances that were beyond me.” whinged the Purple-nosed One, in evident ignorance of the deliberate handball provisions – but perhaps aiming to justify Bruce’s undignified and almost psychotic protest at the time. And the massed ranks of the Kop Choir had to regale the departing Man U fans with victory taunts as they sulked away, silent and crestfallen, headed for all points south.

I can’t remember the journey home, or even how spectacularly ill I was when I got there, although I’m told I was the picture of ecstatic yet grossly hung-over ebullience. I just know it was my happiest Christmas Eve ever, ensuring a deliriously festive spirit for the whole holiday, much to the delight of my long-suffering wife and two-year-old daughter.

Merry Christmas, everybody! And God bless us, every one. Except Them, from There.

Next: Memory Match No. 4: Leeds United 4, Derby County 3. 1997-98 included a purple patch for Leeds United, and a series of “comeback wins”. Perhaps the best was this recovery from 3-0 down at Elland Road against the Rams.

As a former Welfare Rights Worker with C.A.B. in Pontefract and Wakefield in West Yorkshire, I’ve retained an interest in social policy developments in general, and Welfare Benefits legislation in particular. You may take the boy out of advice work, but you can never quite take advice work out of the boy – and the

As a former Welfare Rights Worker with C.A.B. in Pontefract and Wakefield in West Yorkshire, I’ve retained an interest in social policy developments in general, and Welfare Benefits legislation in particular. You may take the boy out of advice work, but you can never quite take advice work out of the boy – and the