The formative years of my early childhood were spent at No.39 Bondgate, Pontefract, which was one of a block of four small two-up, two-down houses situated immediately adjacent to the front entrance of Wilkinson’s Liquorice Works. Our house was about three steps up from the pavement and enjoyed the luxury of a narrow strip of garden, possibly three yards deep. However, we had quite a long back garden which extended up to a brick wall forming the boundary of the gardens belonging to the houses at the top of Bond Street. We children were allowed a free run of the back garden as Dad was never much of a gardener; consequently the word ‘garden’ was a rather optimistic name for our playground.

I have hardly any recollections of the first two years of my life when we lived in a tiny cottage situated on what was known as Little Hill, which is now a grassed area at the bottom of the Booths. My parents’ families lived a little further down the road near All Saints’, Mum’s house being at 95 North Baileygate, while Dad lived at 8 Fox Terrace, a row of terraced houses which stretched from North Baileygate up to the Grange Field.

Dad took us for a walk and we came home to find we had a sister!

I was almost two years old when we moved from the Little Hill to No.39 Bondgate and it was probably a day that Mum never forgot, as my sister decided to be born within hours of the family moving into our new home. My brother, who would be almost four and a half years at this time, remembers Dad taking us for a walk to Box Lane and coming back to No.39 to find we had a sister!

If it can be said that most people can remember things and events from around the age of two or three, then it would probably be around 1930 when we and our neighbours still had to use toilet facilities which were primitive monstrosities known as ‘middens’, situated at the top of our gardens. The least said about middens, the better; suffice to say that they enjoyed none of the benefits of modern plumbing. Fortunately for all of us, it must have been quite soon after our move to Bondgate that our landlord, in his generosity, decided to remove the appalling middens and provided, lower down the garden, a block of new flush toilets, which to us were sheer luxury even in the depths of a hard winter.

Life must have been very hard in the thirties for our parents, as Dad’s small wage as a coke ovens worker, had to go a long way. Nevertheless, somehow or other, Mum always made sure we were well-clothed and fed, as well as managing to keep the house looking clean and tidy. Of course, in those pre-war days, only a few houses were blessed with electricity, and most families in Bondgate relied on gas for lighting and coal for heating and cooking.

Mum and Dad paid for our gas by means of a penny slot meter, which meant you were tempting fate if you didn’t have a penny or two around the house. I remember very well that if the gaslight started flickering, the cry would go out, “Mum (or Dad), have you got a penny, t’gas is begging!” Bondgate itself had gas lamps and Mum had an uncle who worked at the gasworks, part of his job being to walk around Old Church every night, lighting lamps with a long pole, reversing the process at dawn.

The ground floor at No.39 consisted of a stone-flagged living room, a kitchen at the back, and in-between was the staircase under which we kept the coal. The focal point of the living room was the Yorkshire range which shone with weekly applications of ‘blacklead’ and provided both heat from its coal fire and an oven, from which Mum provided mouth watering Yorkshire puddings, the equal of any in Old Church, not to mention her tasty stews and delicious rhubarb pies.

The only equipment in the kitchen was a sink with a cold tap and a ‘copper’ or ‘set-pot’ in the corner which provided hot water by means of a coal fire underneath. Bath-time at No.39 was a weekly ritual which entailed filling the copper to the brim and then ladling the hot water into a galvanised bath, probably one bath full for all of us!

We had two bedrooms and while the front bedroom was a reasonable size, the back one was very small, so much so that if you sat at the bottom of the bed, you would almost bump your head on the ceiling. The sash window looked out onto the back yard and it was quite easy, even for us children, to climb out of the window and drop down to the yard below.

Of course, in the thirties, there was no such thing as television so people relied upon the radio for entertainment (or wireless as it was called), or a wind-up gramophone, such as we had. It was an ancient HMV with an enormous horn, and being Dad’s pride and joy our early musical education consisted of a daily mixture of classical overtures, Gilbert and Sullivan and military marches.

In the hard times of the thirties, we young Old Churchers were taught to appreciate the value of money and always looked forward to each weekend when, if funds would allow, we each received our Saturday penny, which after due deliberation we would usually spend in Hudson’s shop which was just across the road from our house. You could buy all sorts of sweets or chocolate for a penny, but often as not we would splurge the whole penny on a lucky bag which would contain lots of different things – toys as well as sweets. We kids thought they were a bargain for a penny, and as well as enjoying the element of surprise in a lucky bag, you could often, if you were very careful, make the contents last right through until Monday or later.

It was occasionally possible to supplement our weekly penny by earning a copper through running errands for neighbours. The one that sticks in my mind was George, a giant of a man who lived on his own in the end house, next to Wilkinson’s. You hardly ever saw George without his cap on, which almost seemed to be a permanent extension of his head, and he had two facial characteristics which fascinated me.

One was the cigarette which was always attached to his bottom lip, apparently defying the force of gravity and never seeming to hinder the endless flow of George’s rhetoric which he would inflict upon anyone who had time to listen. The other was the dew-drop which usually dangled precariously from the end of his nose, probably a by-product of his large consumption of cigarettes and the dusty atmosphere of his kitchen, in which he plied his spare time trade as a cobbler. The interior of George’s kitchen seemed like an Aladdin’s cave to us kids, being a glorious hotch-potch of cooking utensils, cobbler’s tools and having a brick floor which was littered with fragments of leather and footwear, awaiting George’s attention. Quite often, much of the small floor space would be occupied by the somnolent form of George’s faithful companion, a large black Labrador whose own special smell mingled with those of cooking, leather and Woodbines. George never seemed to have time to buy his own cigarettes, so we were able to earn many an extra halfpenny or so by popping across to Hudson’s to keep George well supplied.

Spooky connotations of the ancient ruins of the Priory of St John.

There were plenty of places in Old Church where we children could play more or less safely. The Grange field, across from Box Lane with the adjoining Wash Beck provided endless scope for our games, though some of us were rather wary of playing there after dark because of the spooky connotations of the ancient ruins of the Priory of St. John. Another favourite place for us was the culvert which carried Wash Beck through the railway embankment, starting behind the Scout Hut and emerging just east of the railway bridge which spanned Knottingley Road. We gave this dank, dark and no doubt rat-infested tunnel the name of Big Ben and even though it was hard to see when we were halfway through, because of a bend in the middle, we would spend many happy hours paddling through its cool water during the seemingly endless hot summers of our childhood. We children were quite oblivious to the dangers of slippery stones and broken glass and it was therefore inevitable that one day I had to hop the 200 yards back to No.39 with blood streaming from a deep cut in my foot, from which I bear the scar to this day.

Another special place for us boys and our friends in Bondgate was Bubwith House Farm on Knottingley Road which was worked by branches of our family for many years. In the early thirties it was farmed by my great-grandparents, and my grandparents’ golden wedding invitation in 1948 shows that my grandfather lived and worked at Bubwith House at the time of his wedding in 1898. Although I don’t remember my great-grandfather, I have clear memories of my great-grandmother standing outside the front door of No.39, ladling out our milk from the two large churns which she had carried about half a mile from the farm. She was a marvellous old lady who held strong opinions on life in general and the bringing up of children in particular. I can see her now, delivering the daily milk along Bondgate, clad impeccably in a long dress, bonnet and black lace-up boots.

Bubwith House was a fascinating place for us to play and we spent many happy hours there, watching the daily routine of the farm and helping out with little jobs, such as feeding the ducks and hens and collecting the daily yield of eggs. One of our favourite places was the hay-loft where we used to swing around on convenient ropes, each of us claiming to be Tarzan of the Apes. Eventually we would emerge, hot, dusty and thoroughly exhausted and if we were lucky we would be invited into the cool stone-flagged kitchen where we might be given refreshing drinks of home-made lemonade, by the apple-cheeked lady I remember as Aunt Minnie.

On our way home from our visits to the farm we occasionally indulged in pastimes which held the double attraction of satisfying our hunger pangs and also being a little daring, not to mention illegal. We had the choice of two settings for these escapades; we could either go ‘scrumping’ into the orchard (which was situated between the railway and Depledge’s field) or we could raid the liquorice field on the other side of the road, next to Wilkinson’s. At that time, liquorice was quite widely grown in Pontefract, as this was the only area that had the necessary depth of soil needed to cultivate the liquorice plant, whose roots could reach a length of six or seven feet and needed the same number of years to mature. All this was of little consequence to us young villains as we crept into the field, pulled up a few young roots and stole away with our spoils. In those days, most of the local production of liquorice roots was absorbed by the handful of sweet factories which, next to the colliery, was one of the main industries in Pontefract. The long brown roots were processed into a black glutinous extract which was the basis for the manufacture of sweets such as the famous Pontefract Cakes. These sweets and other liquorice novelties were known to us as ‘spanish’, the possible derivation being the import of liquorice extract from Spain. All we had to do to make our stolen roots edible was to knock off most of the soil, clean off the rest with a little spit and then chew away happily at the delicious roots which you could make last for hours. The fresh liquorice had a totally different taste from the Spanish we bought from Hudson’s and of course it had the added attraction that it cost us nowt. You could buy the dried liquorice roots, cut up into small pieces, but it was rock hard and didn’t taste as nice as the fresh roots.

As we become older, we tend more than ever to rely upon our senses to revive evocative memories of our childhood and Old Church certainly gave us plenty of scope in that direction. No Old Churchers could ever forget the wonderful smell and unique taste of fish and chips, as sold by Gledhill’s shop at the corner of Mill Dam for well over half a century. You could buy ‘one of each’ then for 1½d; a penny for the fish and a ha’penny for the chips. It goes without saying that the only way to eat them was with your fingers straight from the newspaper with lashings of salt and vinegar, whilst walking slowly home. Somehow they never tasted quite so good when served on a plate with civilised knives and forks.

Our daily walk to school, initially to the tiny All Saints’ Infants and then up to Northgate Juniors, brought us into contact with many interesting sights and contrasting smells.

No-one who lived in Old Church during the first half of the twentieth century could ever forget the disgusting smell that emanated weekly from the CWS Fellmongering Dept. known locally as t’skinyard. It was situated, probably to the great annoyance of local churchgoers, just across from All Saints’ and it must have been a great relief to all residents of Old Church when it was demolished, probably in the sixties.

Another branch of CWS was in complete contrast to the notorious skinyard. On the other side of the road between Tanner’s Row and the school was the Co-op grocery shop, which I believe was managed in those days by Mr Walker, who provided the Old Churchers with a service which cannot be matched by today’s impersonal supermarkets. There was very little pre-packaging in the grocery trade then, and most things were supplied in the exact amount required by the customer, from sugar in neat blue bags, to butter and lard in greaseproof paper.

A mixed perfume of Mansion Polish and paraffin.

On Tanner’s Row itself, behind the pub at the bottom of the Booths, was a blacksmith’s which I think occupied the site of the original tannery. This was a fascinating place for us to dawdle and watch horse-shoeing and other aspects of the blacksmith’s trade as we made our way home from school. Depending upon whether or not we had any coppers to spare, our journeys home could often be further interrupted by visits to the sweet shops, either the one opposite the Hope and Anchor pub, or Woodward’s at the bottom of Box Lane. Near the bottom of the Booths and adjoining Pease’s shop was Garlick’s general hardware store, within whose cool interior you could buy anything from a dolly blue to a galvanised bath, and which gave out a mixed perfume of Mansion Polish and paraffin. At the bottom of Beech Hill, facing Mill Dam, was Hemmant’s grocery shop, from which came the same sort of smells as those issued from the Co-op just round the corner.

A short way down Mill Dam from Gledhill’s was the factory of Hey Brothers whose main products before the war were various pickles and a good selection of mineral waters. After the war the firm expanded rapidly to become one of the largest suppliers of mineral waters, beers, wines and spirits in the country. The factories of Hey Brothers and Wilkinson’s provided, between them, one of the main sources of employment for the young ladies of Old Church, the choice being either a ‘caker’ at Wilkinson’s or a ‘pickler’ at Hey Brothers.

Certain events of the thirties in Old Church remain more firmly fixed in the memory than others. No-one who lived in Bondgate at that time could ever forget the amazing floods around 1932 when a very heavy thunderstorm transformed Southgate, Bondgate and Knottingley Road into a raging torrent. We were very fortunate at No.39 being a few steps up from the main road, but no doubt the houses opposite, in Amer Place and Bar House Terrace would have had severe problems, as would the little wooden fish and chip shop which occupied a site near the present petrol station.

In the summer of 1939, after years on the waiting list, Mum and Dad were informed that we had finally been allocated a house in Willow Park so our ten years in Old Church began to draw to a close. We ‘flitted’ from our little two-up, two-down in the last week of August, a few days before our country declared war upon Nazi Germany on the first Sunday in September. I remember all of us huddled round our wireless at 11am that morning, listening to Neville Chamberlain reading the declaration of war which was also a tacit admission that his ‘peace mission’ to meet Adolf Hitler in Munich in 1938 had been an abject failure. Chamberlain was replaced as Prime Minister by Winston Churchill after the disaster of Dunkirk, and died, within the year, a broken man.

To us children the war ahead seemed an exciting prospect, although most people seemed to think that it would be ‘all over by Christmas’, with our country victorious over the hated Nazis. Little did we know that it would be six long years before the bells of peace rang out and the impact of a hard war, combined with our move to Willow Park ensured that for our family and many others, life would never be quite the same again.

Even after a lapse of some 74 years, I only have to think back to our childhood at 39, Bondgate, and I am transported to our small front room, listening to ‘In Town Tonight’ which might have been interrupted by the strident clamour of a hand-bell outside, preceding the cry of “Any hot peas?” a favourite Saturday night treat.

On Sunday mornings we were often entertained by the Salvation Army, inviting us to “save our souls”, probably being followed by the bells of All Saints’, calling the faithful of Old Church to prayer.

When I dwell upon these and many other memories, I see again the places where we children played, breathe in the smells of Old Church (good or bad), and taste the juicy sweetness of our scrumped liquorice root, and the years roll back as if it were only yesterday.

Happy days! Childhood days!

Ken Atkinson

Ken Atkinson was born in Pontefract in 1927, and has lived there all his life. His career encompassed several distinct phases; Bank teller, National Serviceman (Served in the Middle-East, Palestine, Suez etc), Teacher and – labour of love, this – gardener in the exquisite back garden at No.49.

Ken met Lesley, my mother, in the fifties and they were immediately happy together and deeply in love. Then they got married, and have fought like cat and dog for the 54 years since (only kidding!)

Lesley and Ken had a family of three boys, getting it right first time but still adding two spares, and they have also added various cats over the years.

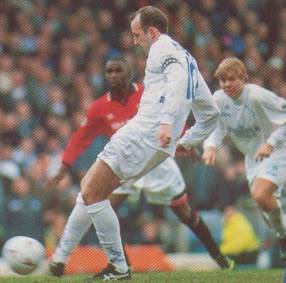

Dad is the man I blame for infecting me with my love of Leeds United, but he was also a dab hand at wine-making, milk jelly, chocolate-covered coconut (better than a Bounty Bar), DIY including bespoke teenage bedroom furniture, Christmas trifles and many other such indispensable talents, so the balance is to his credit. Just.

I would like to thank my Dad for his contribution to my humble blog, and also take this opportunity to apologise most sincerely for that time I got home pissed and was sick down the wall below my bedroom window.

Sorry, Dad.